Reclaiming the Nairobi River: How Youth-Led Clean-Ups Are Restoring Water, Dignity, and Hope

The River Ran Black

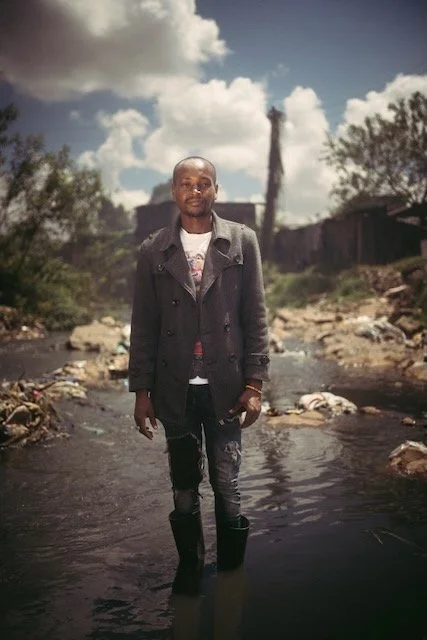

Fredrick Okinda stands knee-deep in the Nairobi River, pulling a sodden mattress from the black water. Behind him, twenty young people from Korogocho wade through plastic bottles, industrial sludge, and waste no one wants to name. Volunteers have encountered bodies during restoration work — a grim reminder of the river's role as a dumping ground for more than just garbage.

"The change we need?" Fredrick says, hauling the mattress to shore. "We are the only ones who can make that change."

The Nairobi River was once a lifeline. For generations, communities like the Maasai, Kikuyu, and Kamba relied on its clean water for agriculture, livestock, and daily needs.[1] But decades of rapid urbanization, unregulated industrial growth, and inadequate waste infrastructure have turned the river into one of East Africa's most polluted waterways.

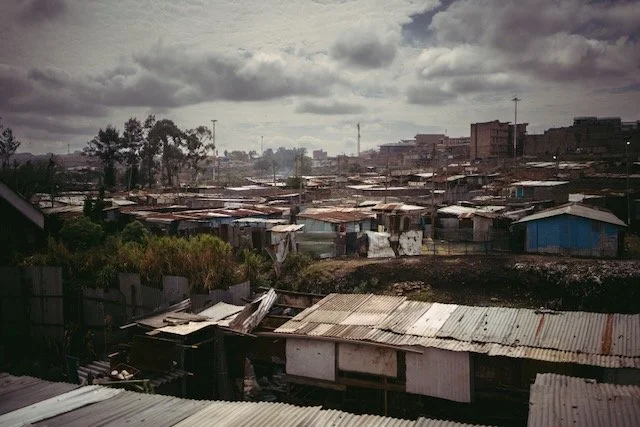

Today, over 5.4 million people — more than half of Nairobi's population — live along the Nairobi River Basin. Most reside in informal settlements like Korogocho, Kibera, Mathare, Dandora, and Mukuru.[2] For them, the river's pollution isn't an environmental statistic. It's a daily health crisis.

The Kenyan government has launched ambitious restoration efforts, including a multi-billion shilling Nairobi River Regeneration Project aiming to reduce pollution by 90 percent by 2027.[5][6] But in Korogocho, one of Nairobi's largest informal settlements, young people weren't waiting for top-down solutions. They were already organizing their neighbors, rolling up their sleeves, and reclaiming their river.

Why Water Is Never Just Water

Before understanding what Komb Green Solutions has achieved, it's essential to understand what was at stake.

Access to clean water is about more than survival. It's about dignity.

Residents along the Nairobi River face daily exposure to contaminated water. Waterborne diseases like cholera, typhoid, and diarrhea are common. Children play near toxic waste. Families wash clothes and grow vegetables with polluted water.[3]

Women and girls bear the heaviest burden. They're more likely to experience violence when using distant or unsafe toilets. They carry the responsibility of water collection. They face heightened health risks as primary caregivers managing illness in their families.[4][8]

The daily struggle to find safe water, navigate unsafe sanitation, and protect children from contaminated play areas takes a profound toll. High rates of waterborne diseases burden families. Chronic exposure increases long-term health risks. The psychological weight of constant vigilance against invisible threats wears people down.[3]

River health and public health are inseparable. Polluted rivers contaminate shallow wells, urban farms, and even piped water — especially in settlements with poor infrastructure. Improving river water quality isn't just about ecosystem restoration. It's essential for reducing disease, restoring dignity, and achieving universal access to clean water and sanitation.[3]

This is the context in which Komb Green emerged — not as a feel-good environmental project, but as a matter of survival and dignity.

Korogocho Wasn't Waiting

In 2017, Komb Green Solutions was founded by Fredrick Okinda, Christopher Waithaka, and other young people from Korogocho. Many had lost friends and family to violence. They had watched their river turn toxic. And they had a choice: wait for someone else to fix it, or start now.[7]

Their answer was to organize their neighbors and start restoring the river themselves.

Christopher Waithaka and several other founders came from backgrounds many would have written off. They had been involved in gangs. Some had criminal records. They had seen too many of their peers killed — fifty young people from their community lost to mob justice, gunfights, and police killings between 2015 and 2017.[7]

But in 2017, when a bridge construction project temporarily employed local youth, something shifted. As the project ended, Christopher, Fredrick, and the rest of the team refused to let their community slide back. They chose a different path: environmental restoration as community transformation.

"Let's not wait for some people to come and change us," Fredrick explains. "The change starts from us."

Month after month, youth and residents gather along the Nairobi River's banks in Korogocho to remove plastic waste, garbage, and debris by hand. They've encountered bodies. They've faced hazardous waste and toxic sludge. Persistent upstream pollution means the river continues to carry new contamination downstream, threatening to undo their progress.

But the community keeps showing up.

"Mostly, you find at the market, you find the plastic bags being sold, but most of them, they're being washed into the toxic Nairobi River," Chris Waithaka explains. "The community took it upon themselves to restore the river, even without financial support."

The work has created visible change. Children who once played near contaminated areas now have reduced exposure to toxic waste. Stretches where Komb Green installed gabion walls for flood control experience fewer flooding incidents. A growing network of residents now see themselves as stewards of their environment, not passive victims of pollution.

Beyond the physical labor, Komb Green organizes monthly community dialogues where residents discuss sanitation challenges, advocate for better waste management infrastructure, and plan next steps together. They've mapped pollution hotspots and water flow patterns. They train youth in environmental awareness and waste management. They work with local authorities to address upstream pollution sources — though progress is slow and frustrating.

"What motivates me is to see more lives being saved through environment," Fredrick explains. "We lost too many people to crime in this area. Transforming these spaces saves lives."

The transformation extends beyond the riverbank. Komb Green reclaimed a former dumping ground along the river and created a community park and urban farm where 15 youth now work in agriculture and 30 families cultivate vegetables. The space provides a safe gathering point for community organizing and a visible symbol of what's possible when residents reclaim agency over their environment.

But the park is one outcome. The real work is in the ongoing, relentless effort to restore the river itself — and in doing so, to reclaim dignity, safety, and the right to shape their own neighborhood.

Chris Waithaka in the Nairobi River.

From Beneficiaries to Technical Partners

What makes Komb Green's work extraordinary isn't just the river restoration. It's the shift in power and recognition.

Early in their work, Komb Green partnered with the Public Space Network (PSN), a youth-led network of over 50 community groups across Nairobi's informal settlements. Founded in 2016, PSN brings technical expertise in participatory urban design, youth mobilization, and advocacy. PSN has established partnerships with UN-Habitat, Nairobi City County and international research institutions — and critically, PSN holds implementation authority.

Partners like Dreamtown provide funding and technical support as needed, but all contextual decisions — choosing communities, adapting designs, engaging government — stay with the local organizations. This ensures that Komb Green and similar groups retain ownership and flexibility, rather than being constrained by rigid external project requirements.

This model has enabled Komb Green to move from marginalized residents to recognized technical partners. Youth who were once dismissed as "at-risk" — or worse, as criminals — now advise the Nairobi County government on urban planning. They lead trainings in climate adaptation, hazard mapping, and nature-based solutions. They demonstrate what's possible when communities have resources, recognition, and the freedom to lead.

The transformation is personal as well as structural. Christopher, Fredrick, and their peers have moved from survival mode to leadership. They've proven that young people don't need saving. They need space, support, and the chance to build something worth protecting.

Systemic Barriers Remain

Komb Green's success doesn't erase the systemic challenges — and it's important to name them.

Persistent upstream pollution continues to threaten the work. Waste from industries, informal settlements, and markets upriver washes downstream daily. Without coordinated action across the entire watershed, community efforts remain fragile.

Funding is limited and uncertain. Volunteers work without pay. Basic tools and materials are scarce. Large-scale government projects can disrupt community-built spaces if not carefully coordinated — recent demolitions and riverbank expansions have shown this risk.[9]

Policy and governance gaps remain significant. Poor enforcement of environmental laws. Inadequate inclusion of informal settlements in city planning. Limited recognition of community expertise. These create ongoing barriers that no amount of volunteer labor can overcome alone.

Kenya's progress on SDG 6 remains uneven. While national access to improved water sources has increased, urban informal settlements lag far behind. The country is not on track to fully achieve SDG 6 by 2030.[10][11] This makes community-led action not just helpful, but essential.

Research shows that urban green spaces improve physical and mental health, social cohesion, and climate resilience.[12] In informal settlements, these spaces provide safe places for children to play, reduce heat and flooding, foster community pride, and create economic opportunities through urban farming and small enterprises. They are not luxuries. They are essential infrastructure for survival and well-being.

But recent years have seen renewed commitment. The Nairobi River Commission and multi-billion-shilling investments signal government willingness. The key is integrating grassroots expertise and ensuring that vulnerable communities aren't displaced or excluded. Komb Green and PSN have demonstrated that youth and community groups can be powerful advocates and technical partners when given recognition and resources.[5][6]

The private sector also has a role. Industry remains a major polluter, but can become a partner through improved waste treatment, investment in green infrastructure, and support for community initiatives.[9]

The path forward requires collaboration — but collaboration where community voices lead, not follow.

A Blueprint for Cities Everywhere

Komb Green's story offers lessons far beyond Korogocho.

First: youth aren't problems to be managed. They're the most effective agents of change when given space, resources, and recognition.

Second: community ownership isn't a nice-to-have. It's the foundation of sustainable transformation. Top-down projects fail when they ignore the people who will live with the results.

Third: green spaces in informal settlements aren't luxuries. They're essential infrastructure for health, safety, dignity, and climate resilience.

Fourth: progress on global goals like SDG 6 depends on connecting international ambition to local action — and letting communities lead the way.

The Nairobi River restoration efforts, led by Komb Green and supported by PSN and Dreamtown, are a testament to the power of community agency in advancing environmental justice. By reducing pollution and empowering youth and women, these grassroots changemakers aren't only restoring a river. They're rebuilding hope, dignity, and resilience in Nairobi's most vulnerable neighborhoods.

On the banks of the Nairobi River in Korogocho, the water still runs dark in places. Upstream pollution hasn't stopped. Funding remains uncertain. Government coordination is incomplete.

But where Komb Green works, children play on ground that was once toxic. Women gather in a garden that was once a dumping ground. And young people who were written off — some with criminal pasts, some who lost friends to violence — now advise the city government on climate adaptation.

The river isn't fully restored. But Fredrick, Christopher and their neighbors have proven something cities everywhere need to see: youth don't need saving. They need space, resources, and recognition to lead.

When cities give them that? Everyone benefits.

That's the power of ownership. That's the future of urban development. And it starts with young people like those in Korogocho — showing the rest of us how it's done.

Bibliography & Further Reading

[1]: KIPPRA. "Restoring the Nairobi River Corridor." https://kippra.or.ke/restoring-the-nairobi-river-corridor

[2]: Wikipedia. "Nairobi River." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nairobi_River

[3]: ScienceDirect. "Impact of organic pollutants from urban slum informal settlements on sustainable development goals and river sediment quality, Nairobi, Kenya, Africa." https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0883292722002724

[4]: Frontiers in Public Health. "Sanitation-related violence against women in informal settlements in Kenya: a quantitative analysis." https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/public-health/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1191101/full

[5]: The Star (Kenya). "Nairobi banks on river revival to transform the city by 2027." https://www.the-star.co.ke/news/2025-09-05-nairobi-banks-on-river-revival-to-transform-the-city-by-2027

[6]: The Star (Kenya). "Nairobi River regeneration reworking slum sewer mess." https://www.the-star.co.ke/news/2025-04-10-nairobi-river-regeneration-reworking-slum-sewer-mess

[7]: Trvst World. "Komb Green Solutions - Creating Nairobi's First 'People's Park'." https://www.trvst.world/regenerative-development/komb-green-solutions

[8]: Frontiers in Water. "Gender equality approaches in water, sanitation, and hygiene programs: Towards gender-transformative practice." https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/water/articles/10.3389/frwa.2023.1090002/full

[9]: The Star (Kenya). "Nema raises red flag over Nairobi river project, fears for health of neighbouring slum communities." https://www.the-star.co.ke/news/2025-09-10-nema-raises-red-flag-over-nairobi-river-project-fears-for-health-of-slum-communities

[10]: SDG Index and Dashboards. "Kenya SDG 6 Progress - Sustainable Development Report 2025." https://dashboards.sdgindex.org/profiles/kenya

[11]: United Nations Kenya. "Steady Gains Against Global Headwinds: Kenya's Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals." https://kenya.un.org/en/280259-steady-gains-against-global-headwinds-kenya’s-progress-towards-sustainable-development-goals

[12]: ScienceDirect. "A bottom-up perspective on green infrastructure in informal settlements: Understanding nature's benefits through lived experiences." https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1618866724000281